How do I know the world has always been a most dark and unromantic place? Even Alex Ross is out here getting the shaft.

The man behind some of comic’s most triumphant visuals made headlines this week when he revealed that he hadn’t been paid by DC and Warner Bros for his efforts. Specifically, Ross explains how CW shows like The Flash and Legends of Tomorrow pulled inspiration from Kingdom Come, his landmark effort alongside writer Mark Waid. (Not to mention Batwoman, a character he helped redesign and overhaul.) To be clear, Ross has been paid in the past, noting that he’d received a few hundred bucks as recently as last year for his efforts appearing in Black Lightning. However, it’s the more recent work that the companies have sampled without paying the proverbial toll. (While the reasoning isn’t clear, there’s one contender: with layoffs all across parent company AT&T, including recent cuts at DC, the decision could be in the interest of streamlining spending.)

As a rule, I’m fully on Ross’ side; creators are perpetually and criminally underpaid, and any chance to address that gives power to long-suffering artists. But I’m more interested in this story than beyond the mere outrage. Ross picks up on a really important thread: how do we pay creators in a new and strange media environment, especially given the structure of comics.

It’s probably important to note that, given some of Ross’ comments, studios don’t have to pay artists and writers, unless there’s some kind of legal action brought forth, which Ross himself also touched on tangentially. Rather, it seems like from what Ross said, this practice of “installments” seems instead like a way to honor the original work of creators (and perhaps for big companies to protect themselves from said lawsuits). There’s also the matter of who owns properties like Kingdom Come; IP stuff can be tricky, but there’s a good chance that DC is well within their rights in giving these elements up for the CW to adapt. So, basically, they can stop payments ’cause they say so.

So I think this as less of addressing a legal issue, then, and more about defining an industry practice. In doing so, we can understand a new system to pay and tribute creators, especially as their works are adapted for TV and movies. Given how profoundly lucrative the comics-Hollywood relationship has been, and will be in the years to come, it’s an important convo to have right now.

There’s something to note beforehand, though. Perhaps like few other mediums, self-referencing is a massive pillar of comics as a whole. All great stories are built on things that have been done in the past; these characters exist as a kind of living quilt, with stories and identities built patchwork over the span of many decades. It’s an industry where everyone is constantly standing on the shoulders of giants, and characters take on these mythic qualities because we all share in telling their story as a collective.

As neat and life-affirming as this process might be, it complicates the idea of adaptations. Using Kingdom Come again, do you then also have to pay the creators of the original characters? What about storytellers who wrote the modern versions of the characters than Waid and Ross then modified? There’s a lot of questions floating around here, and it just demonstrates how comics aren’t as clear as some other channels (music, movies, etc.) when it comes to payment and adaptations and the like.

So what’s there to be done exactly? I think comics should take a cue from the music industry and adapt rules for sampling royalties. Because that’s exactly what Ross is speaking about: one group taking his work, spinning out the elements they want, and creating something new as a result. Just replace that sick bass line with Batman’s exoskeleton.

When considering things like sampling, there’s a few key things to actually address:

(I’d like to make it clear right now that I am in no way shape or form a legal expert. Or an expert in any kind. This is all just one guy’s reading of the proceedings and subsequent advice, and experience in the music biz, trying to understand the issue in a very hypothetical sense. So don’t think of this as advice and more food for thought, like a sweet mid-day snack.)

The “Myth” of Fair Use: In the music world especially, there’s a long-standing belief about fair use that seems to protect samplers. Only, it doesn’t matter if you only take two seconds of a drum loop, you’re still infringing on someone’s copyright, according to entertainment lawyer Adam C. Freedman. That’s because, as Freedman goes on to explain, fair use is often hard to prove within a court setting, as it addresses slightly nebulous ideas like how much you’re changing of the original song to make something new (often via the smallest component) and if said sample does financial “harm” to the artist/original copyright holder. (There’s other considerations here, too, like if you can maintain ownership of certain things that amount to noises and pre-determined chord structures.) As Nolo.com pointed out, folks can always argue fair use, but it often depends on where a judge lands regarding copyrights.

So, one thing is fairly clear: sampling means having to go through the proper channels. Those who don’t, and fragrantly rip off others, open themselves up to a whole nasty can of worms. Just ask Mark Ronson…

Mind Your Manners: Legal experts across the board will advise most artists that it’s important to ask an artist/copyright holder’s permission before sampling. Again, they don’t have to, but channels exist like this to save everyone the headaches. Using the Ross/DC/Warner example again, it’s clear that, from a legal standpoint, the latter two parties don’t have request anything. (Although past payments indicate at least something resembling a legal standing for Waid and Ross, otherwise they’d have never gotten a dime at all.) But this latest round of “usage” indicates that Ross and Waid were clearly never consulted, and while that probably doesn’t sting as much as lost revenue for your artistic work, asking and fostering some engagement go a long way. Ross, at one point even admits they’d even just like a “token of acknowledgement” for their efforts.

There’s been instances of people not having to pay for music samples because they asked, which proves that some artists want to feel in control of their works. That’s not an excuse not to pay, but if Alex Ross’ comments are any indication, it’s a lack of involvement that may be just another slap on the face. Sampling and royalties and general copyright issues are deeply nuanced and complicated, and it’s something all parties need to be involved in so hurt feelings don’t break down into endless lawsuits.

Cash Money is King: So, just how much does a musical sample cost? Well, that depends on the situation itself. There’s been instances where the sampling artist pays as much as 50% of recording royalties for just three to five seconds of “song”. Sometimes music publishers can charge up to $3,000 just as a baseline (with fees then added on). There’s also instances where, once a song reaches a certain point, the original copyright holder can earn additional fees/royalties from this runaway hit. It’s almost never a few hundo bucks as a pittance, effectively. It’s not just the lack of payments for existing work, but it creates an issue where creators lose out on subsequent work or waste time with often pointless legal action.

What’s Worth Some Gold?: If we’re extrapolating this to something like comics and comics-related medium, then, it’s much harder to discern the value of individual components. Is using some element of a character, like Batman’s power armor, the same as four seconds of a dope guitar lick? Or, is it more about the significance of what’s been “borrowed”? That’s why most entertainment lawyers and other industry-savvy folks talk about using as little of a sample as possible. It’s not about avoiding spending the money or having to work with copyright holders; rather, it better protects the sampler and streamlines their efforts and eventual costs. The larger point, though, is that a copyright holder clearly has value here, and even if someone uses just a small bit of someone else’s work, they deserve a fair wage. It’s often less about the “token” that is the sample and what its place in the new product does for all parties; copyright law is clearly to uplift creators and let them maintain a say or larger stake. Ideas have value, and that worth never truly ends.

That speaks not only to Ross’ larger complaints but also the value of existing ideas and how more should be done to empower the original artists. It’s not just some little dweeby gimmick (like giving Superman grey hair), but someone’s intellectual property that’s actively on the line. The aim, then, should be to focus on what the new product “earns” — in the case of the Arrowverse and Kingdom Come, so much of what they’re able to do is based solely on Ross and Waid’s efforts, no matter how much different or altered it appears on screen.

Make It New, Baby: Ultimately, there’s no way to skirt payment and implement fair use as some vibranium shield against possible lawsuits. That said, there’s things samplers can do in order to protect themselves, even if they’re still very much a risk. For instance, parody and satire are often seen as semi-protected (see “Weird” Al Yankovic’s entire career). Some musicians will often re-record a sample to make it distinctly their own (even if that somehow feels cheap). And artists can always modify a sample so heavily that it basically becomes something new onto itself.

The point is, even if this isn’t legally sound, it speaks to the value of going above and beyond just aping someone else’s work. There needs to be some level of effort here, and a real demonstration that this new thing is different enough from the original to merit its very existence as a singular piece of art and not just a bad copy. What’s that mean for the Ross situation? Maybe studios can do a better job of expanding upon the source material to innovate even further. Do they have to from a legal standpoint? No way! But if they wanted to stop forking over a few hundred bucks every time (it’s clearly a big deal if they stopped with Ross), it might be a worthwhile goal. Regardless, it’s also clear that what constitutes “new” ideas versus copyright is equally nebulous, and that means more can be done to define these efforts. Comics work because they build off existing stories and characters, and that kind of growth feels like a cohesive effort and not just someone borrowing from everyone else. It’s the difference between a real storytelling tradition and not cheap adaptations.

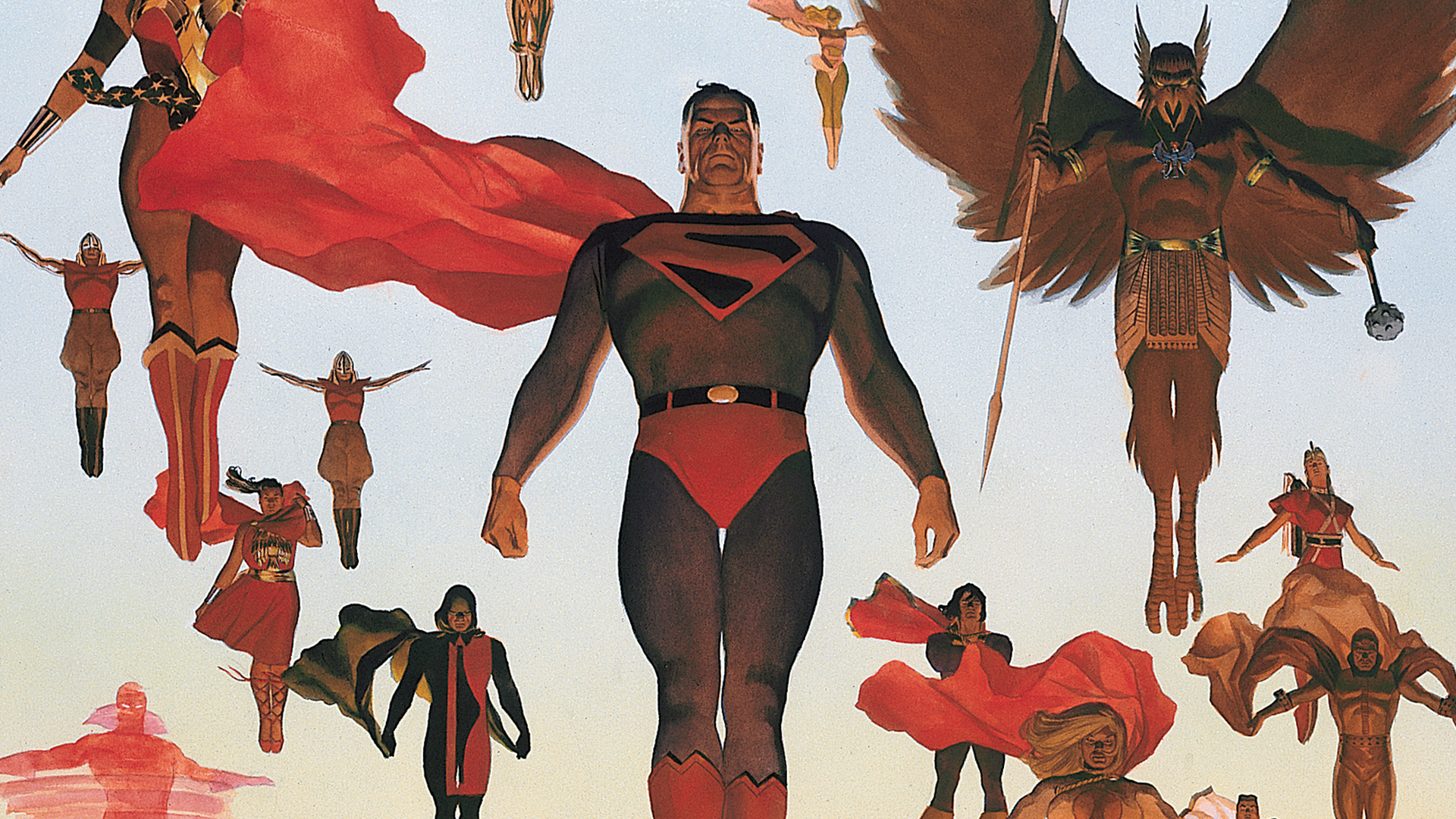

Courtesy of DC Comics.

I get that some of the issues here aren’t so linear (I’m comparing apples to a Mack truck). As well, I’m ignoring layers and layers of legal context, which clearly matter and complicate this massive, massive issue. But as I had said before, I’m not offering a free legal strategy; I’m pointing out a huge issue here. The whole case around Ross’ comments proves that there’s a disconnect going on that’s spitting directly in the face of creators’ rights. Ross and Co. were receiving payments and then it stopped — except Warner Bros. and their ilk still profited from their efforts. These large corporations don’t get to engage in this legal and creative process one day and then decide not to another. If they had to pay once, they have to keep on paying regardless. If they want to do away with the mere bread crumbs they’re having to toss creators, they can always stop using their ideas.

I hope that, if nothing else, some of this essay will prove that comics creators aren’t alone in this issue. The music industry, as just one rather specific example, faces a lot of the same core issues: empowering artists with some level of control, paying them a decent fee/wage for their efforts, honoring the creators’ ongoing role as art grows and becomes remixed (nothing is static!), and holding big corporations and money men accountable for their efforts. Generally speaking, the music industry hasn’t figured out this conundrum 100% of the way — they have, though, made some major steps in providing structure and resources for artists to keep things slightly more equitable. (Spotify, for instance, and its role as a true kingpin of streaming music continues to be a massive subject of debate for artists, labels, etc. There will always be problems of people benefiting from other’s work when they shouldn’t.)

Ross’ comments prove that the same luxuries aren’t always afforded for comics creators and that there’s not even enough of a conversation happening for people to grasp that his issues aren’t merely complaints but indicative of a larger problem. Musicians have recourse for their efforts; comic creators get to go on YouTube and air their grievances. If we don’t think about how to take existing systems to help creators in other, albeit similar fields, we’re sending a really mixed message. And it’s in that resulting space that the creators often suffer. Even if there’s no direct transfer of sampling and copyright law/practices between music and comics, hopefully, creators and fans alike see that there’s still something to be done. The first step comes with recognizing the severity.

At the end of the day, all we can hope for is a conversation to begin around Ross’ comments, and that other creator can become empowered when it comes to protecting their work. I hope that this episode can be the start of a grand awakening, of sorts, that creators deserve not just continued payment but the ongoing respect and acknowledgment that accompanies. Back in 2015, the iconic record label EMI unveiled plans for a “sample amnesty”: anyone who sampled from their massive catalog could keep the royalties if they simply recognized what they had pulled from.

The label, then, hoped that the practice would take off industry-wide, and serve as a way to empower artists in this massive maze of legal and creative proceedings. Maybe Alex Ross’ interview can have the same kind of impact, and let the corporations and creators recognize their connection in a way that promotes a conversation and not further animosity. If that leads to better payment structures and protections for writers and artists, then that’s amazing. But the first step is seeing the scale of the problem at hand.

I don’t have hope for some magical world we all sit around and sing sea shanties together, but a dream of something more sure would go a long way.

Join the AIPT Patreon

Want to take our relationship to the next level? Become a patron today to gain access to exclusive perks, such as:

- ❌ Remove all ads on the website

- 💬 Join our Discord community, where we chat about the latest news and releases from everything we cover on AIPT

- 📗 Access to our monthly book club

- 📦 Get a physical trade paperback shipped to you every month

- 💥 And more!

You must be logged in to post a comment.