Pop quiz! Which American president was also a pioneering paleontologist?

If you didn’t know the answer is Thomas Jefferson, you’re not alone. Between writing the Declaration of Independence, serving as the ambassador to France, authoring the most popular book in America prior to 1800, and his multitude of political positions including Secretary of State, Vice President, and President, Jefferson’s role as an early paleontologist tends to get overlooked in most historical accounts. It also doesn’t help that Jefferson’s paleontological career never involved working with dinosaurs, those Mesozoic celebrities so synonymous with the discipline.

Fortunately, there are two new illustrated children’s books that aim to inform and entertain young readers (3 to 8-years-old) about this missing piece of American scientific history: Bones in the White House: Thomas Jefferson’s Mammoth (Doubleday, 2020) and My Mastodon (Creative Editions, 2020).

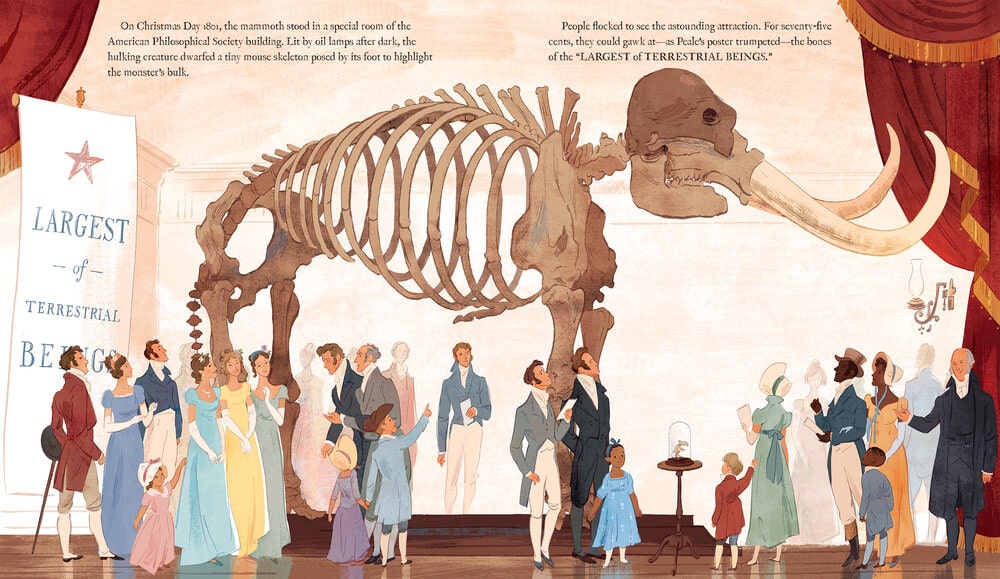

Undoubtedly the strongest aspect of both of these books is their gorgeous full color illustrations. Bones in the White House is drawn by Jamey Christoph, whose style resembles the work of comic book artists like Bruce Timm and Darwyn Cooke. Christoph’s illustrations appear on every page, with many presented as two-page spreads, and the book’s beautifully designed hardcover and matching dust jacket. His work is sure to fire the imaginations of Bones’ elementary school-aged target audience, especially his opening drawing of a ghostly mastodon looming over a moonlit Mississippi River.

Italian artist Antonio Marioni’s illustrations for My Mastodon are equally captivating, while being totally different in style, reminding me of the paintings of Georges Seurat. Several of Marioni’s illustrations are also two-page spreads, with the others being single pages opposite a white text page. In a whimsical touch, though, these drawings seem just barely contained, as little details can be spied escaping into the adjacent negative space. Marioni’s art also graces the dust jacket for My Mastodon, and there’s a small drawing of a mastodon featured on the front of the book’s hardcover.

Accompanying Christoph’s illustrations for Bones in the White House are the words of writer Candice Ranson, whose bibliography behind the back flap of the dust jackets shows she’s clearly done her research. But Ranson’s attempt to whittle down a complex story involving political propaganda and nationalistic science into a simplified narrative for children leaves much to be desired. Jefferson is said to have “a bad case of ‘mammoth fever,'” constantly demanding “more bones!” Eventually Jefferson acquires not only more “mammoth bones,” but those of another creature he dubs “Great-claw,” which he believes to be a lion (but is later revealed to be “an ancient sloth”).

Throughout Bones‘ 40 pages, Ranson never fully explains how the conclusion was reached that the “Great-claw” was a sloth and not a lion, or why Jefferson had “mammoth fever” to begin with (I address the topic here). Ranson also mentions several times that Jefferson wasn’t sure if the mastodon was alive or dead, but never explains why that was unclear or what the ultimate conclusion was.

Still, Ranson’s narrative is at least rooted in science and history, as opposed to My Mastodon, which is completely ahistorical. Author Barbara Lowell’s story centers on the character of Sybilla Peale, the daughter of early American museum proprietor Charles Wilson Peale, who Jefferson dispatches to obtain a mastodon skeleton found in Newburgh, New York, which Peale subsequently mounts for public display.

Lowell’s 32-page story remains focused entirely on Sybilla, who develops her own case of “mammoth fever” as she comes to think of her father’s mounted mastodon as her new best friend. It’s encouraging to see a young girl at the center of a story about paleontology, but the decision to frame it as a tale in which she becomes utterly enamored with a static reconstruction of a long-dead mastodon is a bit odd.

Bones in the White House has its share of odd decisions, too, as Ranson’s choice to continually refer to the prehistoric creature at the heart of her story as a “mammoth,” even though the correct scientific designation is “mastodon,” as observed by Lowell. The last page and interior back cover of Bones contains several historical notes by Ranson, one of which offers some clarification on the difference between a “mammoth” and a “mastodon,” and explains that her use of antiquated jargon was for historical authenticity.

The longest of Ranson’s notes, “Jefferson in History,” also addresses the complicated issues of Jefferson’s role in the institution of black chattel slavery, and in advancing the displacement of the indigenous inhabitants of North America. In explaining these facts, Ranson acknowledges that Jefferson unquestionably benefitted from the institution of slavery which, among other things, allowed him “the freedom to pursue his interests,” including paleontology.

Ranson also notes that Charles Wilson Peale likewise owned enslaved peoples and that one of these men, Moses Williams, played a key role in helping Peale assemble his mastodon skeleton. Williams is depicted in one of Christoph’s illustrations but is not actually mentioned in the narrative itself. Even if confined to notes, Ranson and Christoph’s decision to addresses these difficult topics should be applauded as they are entirely absent from Lowell and Marinoni’s My Mastodon.

Despite such quibbles, both Bones in the White House and My Mastodon are commendable contributions to an already mammoth body of children’s literature, if only because they do not deal with dinosaurs and choose instead to highlight a different but equally exciting aspect of the field of paleontology.

AIPT Science is co-presented by AIPT and the New York City Skeptics.

Join the AIPT Patreon

Want to take our relationship to the next level? Become a patron today to gain access to exclusive perks, such as:

- ❌ Remove all ads on the website

- 💬 Join our Discord community, where we chat about the latest news and releases from everything we cover on AIPT

- 📗 Access to our monthly book club

- 📦 Get a physical trade paperback shipped to you every month

- 💥 And more!

You must be logged in to post a comment.