It’s been nearly twenty years of Walking Dead media. From its original comic book, the franchise has moved into television, animation, and, reportedly, future feature films. It has been board games, card games, and tabletop miniature games. It has been both video games and novels; it’s even a theme park ride.

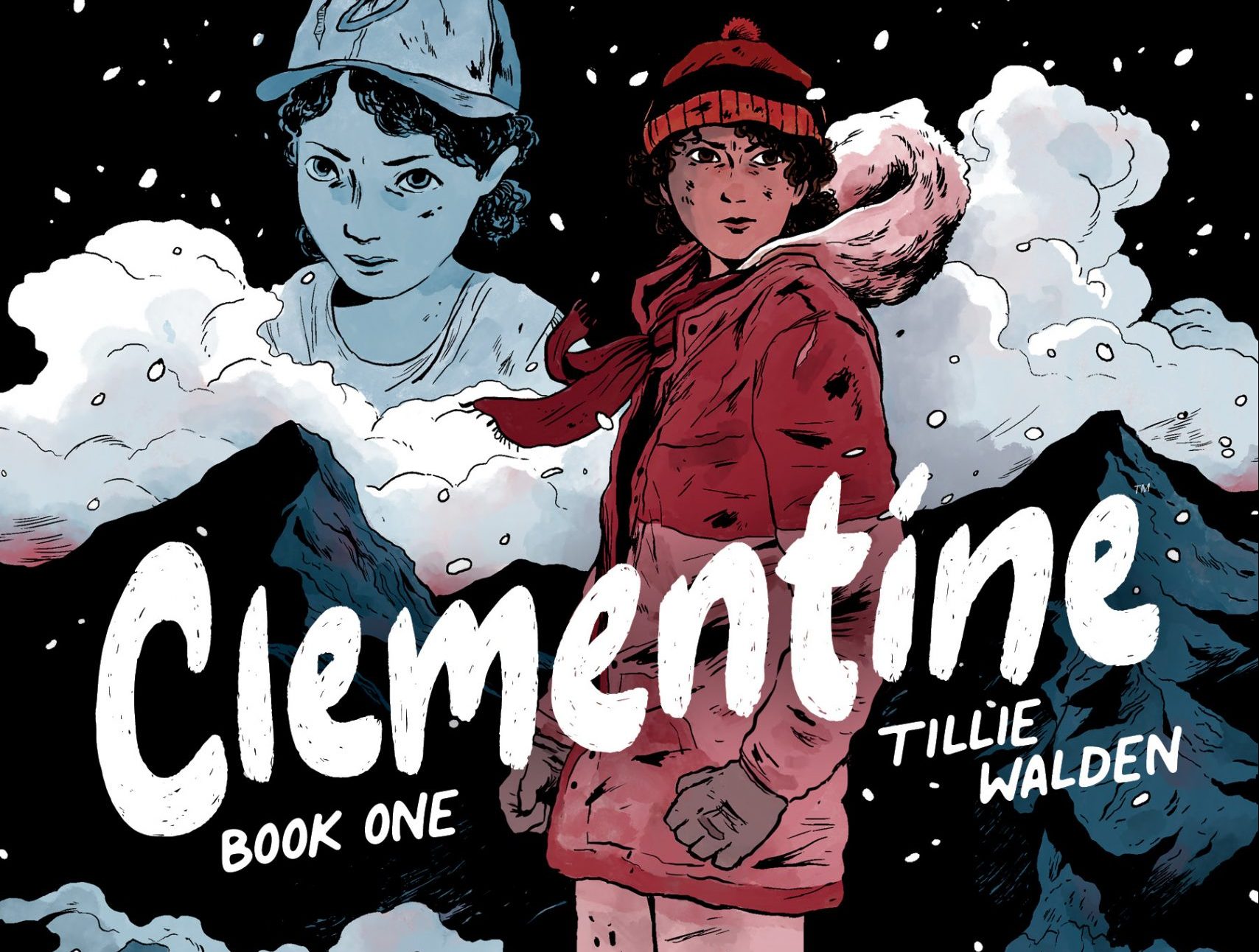

Until this week’s release of Tillie Walden’s Clementine, it had never been an unquestionable masterpiece.

I’m certain longtime fans will have a lot to say about that — there are lists about the best episodes, the scariest issues; closer at hand (and more germane to this conversation) are the critical darling adventure games from now-defunct Telltale Games, from which the character of Clementine originates.

Disconnected from the overwhelming mythology of 193 issues of comics or 131 hours of television (discounting spinoffs in both genres), The Walking Dead games were more compact, more urgent. There wasn’t a lot of room for straying from the most powerful and concise narratives, characters, or jarring plot developments.

With Clementine, Walden crafts something altogether other, not only from the larger franchise but also the ostensible source material; where the stories of Clem’s childhood (as related in The Walking Dead seasons 1 through 3) were filled with high-stress horror, gunshots, and morally gray snap decisions, Clementine tells a quieter, more reflective story.

Washed out in grays by collaborator Cliff Rathburn, Walden’s bold black and white often feel like one of reflective repose, even when crawling with the living dead; at this point of the apocalypse (and, more importantly, at this point of Clem’s life), the horror and violence of zombies is a wholly natural aspect of the world.

The true horror of the book shines through Clementine herself, not when she’s enacting violence but when she’s trying to process it. On a snowbound mountaintop, with a handful of other young survivors, Clementine is forced, perhaps for the first time, to stop moving. The constant movement of a survivor on the run, adrift on the winds of the apocalypse, has kept her from thinking too deeply about her state of being, her experiences, or on her loss.

Several times, Clementine’s companions ask her about herself, or simply offer up their own experiences, and each time Clementine closes the conversational gambit down. Loss, violence, and trauma have made shaped her into a grim presence, one deeply unwilling to make connections. Any connection she might make — as with every single supporting cast member of her video games — is sure to end in tragedy.

These narrative concerns are never overblown; Walden seems incapable of working with anything but subtlety. Under her care, Clementine is a book that all but refutes its own franchise; there are no screaming madmen, no cannibals or prison wardens or obvious societal metaphors here. The bloody violence is restricted, literally buried in snow, and the titular dead are mere setting context. Instead, Clementine is honest, personal, and resonant, a story that speaks to the reader rather than at them.

There is room for any number of stories after the world has died. This one, however, feels the most like living.

Join the AIPT Patreon

Want to take our relationship to the next level? Become a patron today to gain access to exclusive perks, such as:

- ❌ Remove all ads on the website

- 💬 Join our Discord community, where we chat about the latest news and releases from everything we cover on AIPT

- 📗 Access to our monthly book club

- 📦 Get a physical trade paperback shipped to you every month

- 💥 And more!

You must be logged in to post a comment.