In a 2014 interview to promote the book The Cryptozoologicon (2013), artist John Conway defined cryptozoology as “entertaining the notion that legendary beasts are real animals.” This may sound like a strange definition to those used to conceptualizing cryptozoology along etymological lines (as the “science of hidden animals”), but it’s actually a very concise summation of the methodology of Bernard Heuvelmans, the self-styled “Father of Cryptozoology,” as found in his book The Natural History of Hidden Animals (2007). According to Heuvelmans, the primary aim of the cryptozoologist is to try to imagine what the fantastic beasts of myth and legend might be like as real animals; an endeavor which Conway’s co-author, paleobiologist Darren Naish, has dubbed “speculative creature building.”

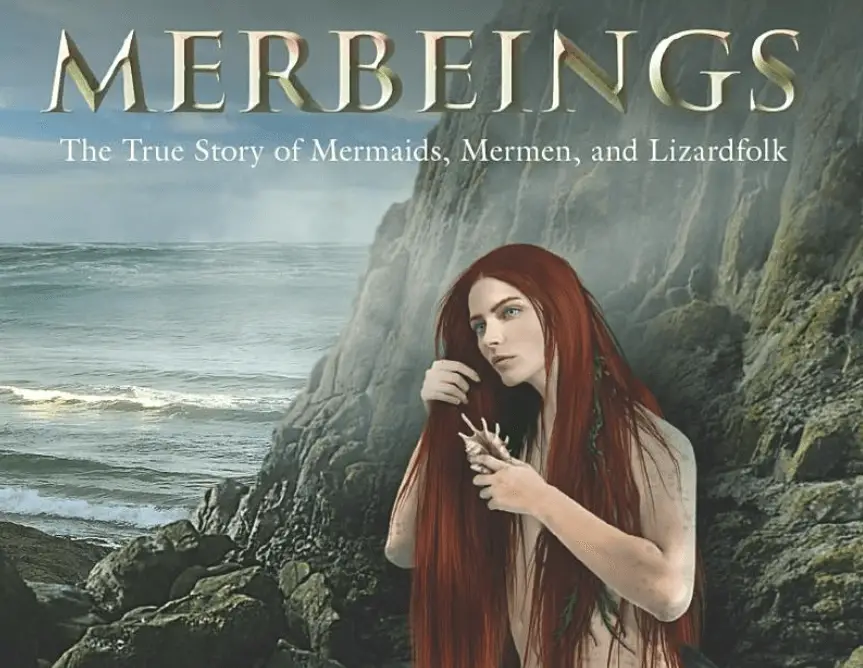

Undoubtedly among the boldest of cryptozoology’s speculative creature creators was the late Mark A. Hall (1946-2016), whose talent for cryptid conjecture is on full display in his posthumously published Merbeings: The True Story of Mermaids, Mermen, and Lizardfolk (2023). Recently brought to press by Anomalist Books under the editorial guidance of fellow cryptozoologists Loren Coleman and David Goudsward, Merbeings runs just shy of 200 pages and represents the culmination of Hall’s lifelong interest in the possibility of amphibious primates.

Merbeings begins with a discussion of the 2003 unearthing of the fossils of Homo floresiensis, the so-called “hobbits” of Indonesia. Many, including former Nature editor Henry Gee, saw the discovery of Homo floresiensis as legitimizing cryptozoology. Hall, more specifically, argues that Homo floresiensis should be seen as proof that generations of folklore concerning “little people” (e.g. fairies, elves, gnomes, etc.) is rooted in truth.

As a result, Hall reasons that similar mythical humanoids such as giants, satyrs, trolls, and yes, even mermaids, may likewise be real. In this way Hall offers readers the cryptozoologist’s equivalent of Pascal’s Wager: believe in monsters and lose nothing if they turn out to not exist, OR doubt their existence and end up looking foolish when physical evidence for them eventually turns up.

Regardless of what ones thinks of Hall’s epistemological proposition, Merbeings takes readers on a worldwide and century-spanning tour of beliefs in these creatures across human culture. Previous works like historian Vaughn Scribner’s Merpeople: A Human History (2020) have demonstrated that the literal belief in mermaids and mermen was once commonplace, and was until recently endorsed by some of the smartest men in the western world.

However, Scribner’s book only focused on merbeing beliefs in Europe and the Americas, and only up until the early 20th century. Hall’s Merbeings is then useful supplemental reading to Scribner, especially Chapters 7-9, which look at mermaid beliefs in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Oceania, as well as its reports of encounters with such creatures as recently as this century.

Equally fascinating are Chapters 11-12, which consider reports of lizardmen from North and South Carolina, which Hall believes are part of the same phenomena. One attribute of lizardmen which has long puzzled cryptozoologists and skeptics alike are these supposed creature’s tendency to attack motorists while in their vehicles; which seems like an odd behavior for an animal. Hall connects this idea to a longstanding folkloric tradition of ghosts assaulting men mounted on horseback, arguing that lizardman stories are a modern variation of this same motif.

Observations such as these – supported by copious endnotes and a healthy bibliography of primary and secondary scholarly sources – makes Merbeings a worthwhile addition to any folklorist’s library, irrespective of if you agree with Hall’s wilder contentions about a supposed biological reality behind the mermaid myth. He speculates that merbeings are the evolutionary descendants of an extinct genus of swamp-dwelling ape known as oreopithecus bambolii. Rather than dying out at the end of the Miocene (5.3 million years ago), as mainstream paleontologists contend, Hall imagines that oreopithecus survived by becoming increasingly amphibious, and eventually fully aquatic.

Such speculations are not unique to Hall. As discussed in Chapter 9 of Merbeings, in 1982, anthropologist Roy Wagner published an article in the annual journal of the International Society of Cryptozoology (ISC) concerning the ri, a mermaid-like creature reportedly living off the coast of Papua New Guinea. Wager had collected reports of the ri while doing ethnographic field work on the island of Latangai in the late 1970s, and said that the locals swore the ri was no spirit and no myth. Wagner even claimed to have seen one of these creatures himself.

Several scientists critical of Wagner’s article wrote into the ISC warning that if cryptozoology wished to be recognized as a legitimate science, it would need to steer clear of such clearly fantastical creatures as mermaids. But Heuvelmans, who happened to be the ISC’s acting president, defended Wagner by declaring mermaids a completely acceptable cryptozoological, topic as the possibility that they represented “a still unknown form of aquatic primate […] cannot be ruled out completely.”

International Cryptozoology Museum proprietor Coleman has also written extensively about merbeings, though his ideas are rather different than Hall’s. Coleman believes there are at least two types — one whose rear limbs have fused into a dolphin-like tail, and a second type with legs and resembling the Gillman from the movie The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954). Hall only believes in the second type, which is problematic since the vast majority of reports are of the former. Coleman contributes two essays to Merbeings, a biographical sketch of Hall and an overview of a number of lizardman-type cases which Hall doesn’t address. Coleman here speculates that such creatures may be the evolutionary descendants of small theropod dinosaurs.

Many will, of course, find any and all such conjectures concerning the putative biological identity of merbeings meaningless, but as an exercise in speculative creature-building, I’d propose that the mermaid – more than the Sasquatch, Nessie, or even Mothman – embodies the ultimate litmus test for cryptozoologists.

AIPT Science is co-presented by AIPT and the New York City Skeptics.

Join the AIPT Patreon

Want to take our relationship to the next level? Become a patron today to gain access to exclusive perks, such as:

- ❌ Remove all ads on the website

- 💬 Join our Discord community, where we chat about the latest news and releases from everything we cover on AIPT

- 📗 Access to our monthly book club

- 📦 Get a physical trade paperback shipped to you every month

- 💥 And more!

You must be logged in to post a comment.