· Who is Number One? · Wake up, Mr. Freeman. Wake up and smell the ashes. · Maybe there are people out there who are more important than us, more powerful, communicating things in the world that are meant for only them and not for us. · I heard the rumours about how the ant farm was built to contain it. · You are Number Six. · Central might catch up to him before he got there. But lurking behind them might be something even darker and more vast, and that was the killing joke. · We want. Information. · No one, no government agency, has jurisdiction over the truth. · We understand so much, but the sky behind those lights– mostly void, partially stars– that sky reminds us we don’t understand even more. ·

·

Information.

·

You won’t get it.

·

By hook or by crook — we will.

This article contains few spoilers (and many secrets). The quotes above are all taken from X-Files, The Prisoner, Possession, Strange Skies Over East Berlin, Half-Life 2, Under the Silver Lake, Doom Patrol, Authority, and Welcome to Night Vale, respectively. Quotations at the start of each of the following sections are all taken from the series proper.

I.

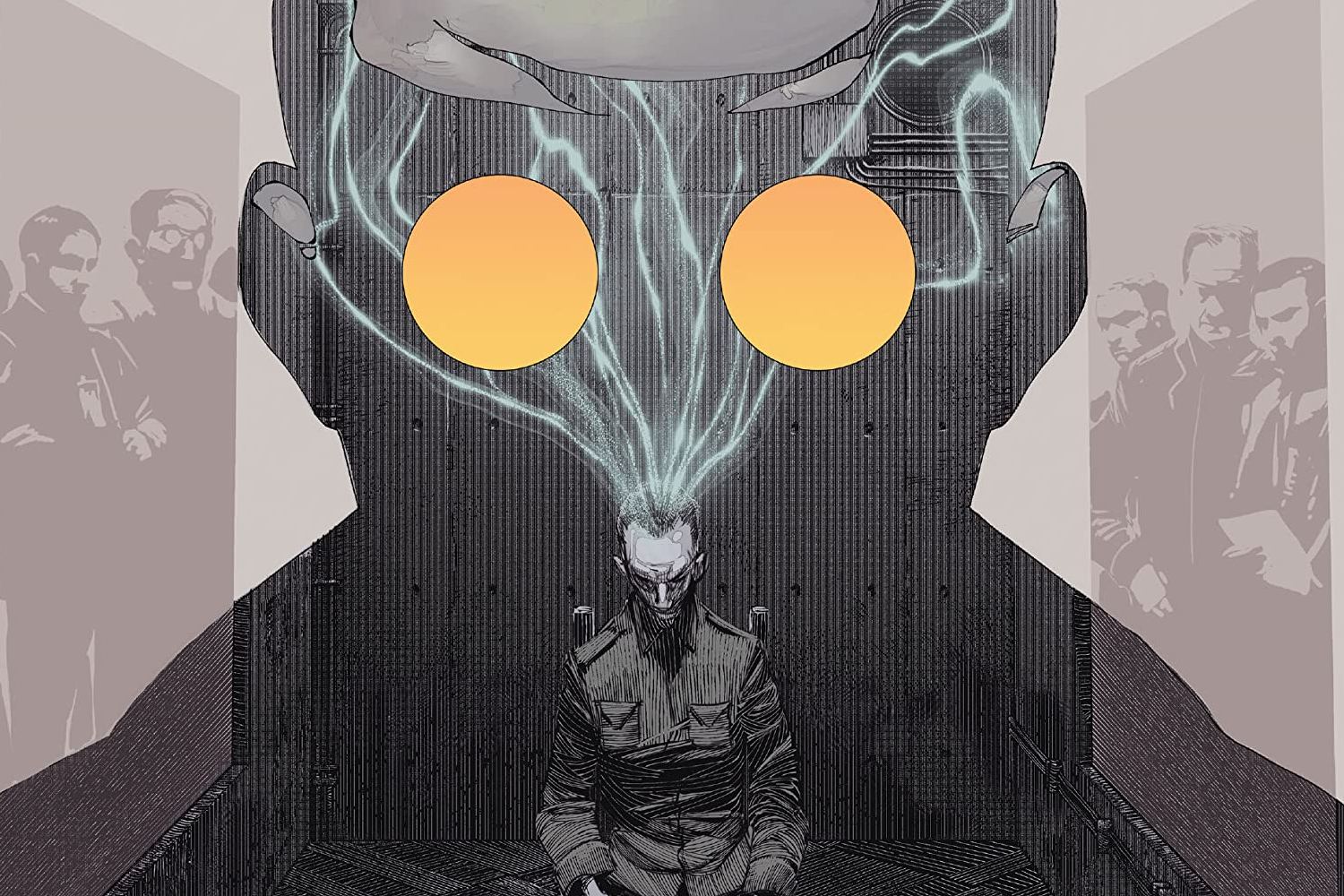

Strange Skies Over East Berlin is a comic in four parts by Jeff Loveness, Lisandro Estherren, Patricio Delpeche, and Steve Wands.

But we’re not going to talk about that for a little bit. First, let’s define our terms.

When we call horror “Lovecraftian,” we typically mean one of two things. 1: The thing we’re talking about is horror that works with the fictional stuffs created by and surrounding the world of HP Lovecraft: Shoggoths, giant squid monsters, weird-geometried cities, and whatnot. 2: Or, we’re talking about horror that’s scary for the same reason Lovecraft’s works were scary: horror about our inability to know fully or understand fully the world around us because of our extremely small and insignificant place in the universe, because it was not designed to be known by us. Some horror we call Lovecraftian because of its tropes, other horror because of its themes. I really wish we had a better word for the latter, because “Lovecraftian” always conjures up images of the former, and because it centers one man who for a great number of reasons should not be centered.

My suggestion– and I understand it’s extremely pretentious, so I’m willing to hear out alternatives– is that we call horror about these themes, but without tentacles, Old Ones, etc., Epistemological Horror. “Epistemology” is the study of how we know things, and even the driest academic texts on the subject can get scary fast. Google Hume’s Problem of Induction or Thomas Kuhn and Paradigm Shifts before you go to bed one night. I dare you.

My favorite example of Epistemological Horror is Ted Chiang’s “Hell is the Absence of God,” but likely the greatest example in our day (and by “greatest” I mean both something like “most likely to still be read a hundred years from now” and “most entertaining”) is Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy. Quite a bit of that trilogy will give you the willies — the Crawler, the Strangling Fruit, the human eyes surrounded by something else — but the passage that always chills me to the bone is just two characters talking about the science and vocabulary of wine-making. Terroir refers to the combination of a million particular circumstances that produce a unique, completely individual cask of wine, a wine that can never be exactly replicated. But what they’re really talking about in that conversation is how the strange place they’ve come to is so strange, and its conditions so far from our abilities of replication, that science as we understand it simply cannot account for that place. The characters can’t know, can’t understand Area X, and by extension it is extremely likely that they will never understand reality itself.

And that’s what will really trouble you if you read the trilogy. In any particular moment, you might be unsettled by a monstrous creature, or a violent encounter, but when you set the book down, what is disturbing is the complete lack of answers to any questions you might have developed by the time the book ends. You probably won’t feel that the author has refused to give you answers, mind you, but rather that the places and events described in this book have no answers that can be comprehended by your extremely human brain. You could never understand what came to the Lighthouse, the goals of Area X, or the verses on the Tower’s walls.

If you only saw the movie, the sort of effect that I’m talking about was dampened but still present at the climax. Think about the strange geometries that rise out of the Biologist’s blood and the weird dance that begins as the alien score swells. Think about how you felt in that moment when you had no idea what the fuck was going on, and think about how you felt later on, when you got home, and you googled “Anihilation ending explained,” and soon it was 3 a.m., and none of the videos were satisfying. Then you woke up without having remembered falling asleep, but now that you were awake, you couldn’t get out of your head that final image of a glimmer in an eye.

Lost is epistemologically-concerned fiction, but I wouldn’t, in the end, call it Epistemological Horror, because you’re given an untroubling answer (even if you think that answer was bad). The Leftovers is closer, because even if it’s not designed to scare the reader/viewer, it is at least designed to confront them with the characters’ ignorance and possible despair, to give the audience some sense of dread. All mystery fiction concerns epistemology, but cozy mysteries are the antithesis of EH, as, no matter how gruesome the murder, there is comfort in the fact that a good detective can know the truth in full and share that knowledge with you. Noir or hardboiled detective fiction, on the other hand, often borders EH. Those grim detectives either fail to arrive at the full story or learn it only through happenstance and chaos, through no process that could be replicated. The noir detective doesn’t solve a mystery through genius. Fate just gives the detective the answer, or else the detective is too damn stubborn to turn aside before the winds of chaos blow it in his face.

I bring up detectives not just to illustrate the genre’s borders, but to show that a story can still produce a feeling of Epistemological Horror even while it gives the reader or characters some sort of answer. Really, our Ur-examples of the genre are all about answers. An answer leads Oedipus to tear out his eyes, but when we put down Sophocles, we’re left in a similar place as when we put down The Southern Reach: we cannot fully understand. We cannot understand fate, or the gods, or the cruelty of the universe.

These things are beyond our mortal ken.

II.

· Make the truth whatever you need to be. · Are we the last two left down here? Trapped with our sins and fear? · One last prayer in the dark. · You know how to get out. ·

So we’ve got our genre. Now let’s narrow our focus.

Our stories in this genre feature, of course, quite a lot of characters concerned with the knowledge: not just scientists and detectives, but also preachers, pastors, prophets, students, scholars, sorcerers, and sometimes even poets, writers, and other artists. The one I want to talk about is the government agent, the G-man, the Man in Black, the spy.

The spy story always, by its very nature, lies just on the edge of horror, and it is always concerned with epistemology. I probably don’t need to do much to convince you of the latter; spy stories are always about secrets. Even the most bombastic James Bond or Jason Bourne movies are narratively driven by secrets (and their revelation or exposure). Take a look for a moment at the trailers of spy thrillers. Notice the way many of these are put together: they’re often closer to horror trailers than action trailers. Their goal is to make the viewer feel unmoored. There will be twists, revelations, conspiracies, and both the viewer and the protagonist are in danger of being overwhelmed by these things.

Spies also feature extremely prominently in our present day horror-folklore. A hundred years ago, if you are in a horror story, and you knew too much, you might meet your fate at the hands of a cultist or the thing cultists’ worship. Today, men dressed in black, with opaque sunglasses possibly covering inhuman eyes, might suddenly appear. Maybe they knock on your door, and let you know they have a few questions. Or maybe they just sit across your street. Watching. Slowly piecing together the extent of what you know.

Spy fiction intersects with the kind of epistemological horror we’ve been talking about. The insanity-inducing unknowable may take the form of vast conspiracies, secret organizations, agents of, as Welcome to Night Vale puts it, “vague yet menacing government agencies.” Even when the protagonists themselves are spies or agents, they often find that, by getting their foot in the door, they’re able to see exactly how unnavigable is the organizational labyrinth of secrets and government levels on the other side. It is not coincidence that Sam Niel in both Possession and Event Horizon is a government agent of some kind. Mulder and Scully are probably the most well known protagonists of this subgenre– but the best example of spy horror (and by “best” here I mean “best” in every possible sense of that word) stars a man known only as Number 6.

If you haven’t seen (the original) The Prisoner, you should correct that.

In the opening sequence of The Prisoner, a British spy resigns from his agency and is immediately kidnapped to a strange island known only as The Village. The Village is an unsettling, bizarre place; it’s probably a Cold War prison run by the Americans, British, or Russians, but it is so deeply weird and powerful that it feels inhuman. It could just as easily be a station of MI6 as a circle of Hell. The Village is devoted to seeking information: specifically, it wants to know a secret of the captured spy’s heart. It wants to know the real reason why he chose to resign.

The Prisoner is not often described as “horror,” I think, but watching it I often feel the same dread that Lovecraft hoped to invoke, the dread of looking at something that is beyond human comprehension. But at the same time, that dread is achieved not through eldritch tentacles, but through extremely human things: the psyche and internal life of a human character, and his relationship to his job, his country, his society. The Prisoner still feels cosmic, though; it posits an unknowable reality through its examination of the psychological, and personal, and political, and I think all spy horror exists in a similar kind of state.

III.

· Secret police on every street. In every letter. Every conversation. Every life. ·

We might have begun in the wrong place. Maybe from an alternate angle, we can see the full picture. Maybe if we try to ground things, we can understand how spies have become such effective successors to Lovecraft, and why Strange Skies is such a powerful example of this genre.

If you grew up anywhere near DC, you might have had a friend whose dad worked for The Government, and whose dad you whispered about, because no one would say what his job really was, and he was gone for great stretches of time. One time he came to pick up his kid from a sleepover, and someone saw, as he opened the door, and his jacket shifted, the glint of a gun.

If you grew up in the ‘90s and ‘00s, you learned in your history classes about the Cold War, about how just a few years prior at any given time, at any given moment, all life on Earth might have been extinguished. There were men hidden away in bunkers, who held secret codes that could burn everything. There was no direct conflict. Instead, there were agents, and double agents, and saboteurs, and compromised officials, all scrambling for power. But all that was over; the Cold War was done, all such wars were done, any wars now were by comparison skirmishes that might result in horror, but would not result in the end of all things. The Berlin Wall had fallen.

In the classroom’s great rush from VJ Day to the present, the Berlin Wall loomed large over everything. Vietnam and Korea were complicated, confusing; the Berlin Wall made the not-war with Russia something tangible. In one city, there was one specific place where you could see the division take form. Your textbook might have had pictures, or diagrams, of watchtowers along The Death Strip. And your teacher might have owned a piece of it, brought in some rubble, and you could hold in your hand proof that we had inherited a safer world.

And if you grew up in America during this time, what came next was, of course, the Towers.

You were told that a strange organization had emerged in what was described as some distant desert, and the people of that organization, well, they hated you — they hated the collective you and you in particular — and anything, your flight, a bus, a letter in the mail, could and would probably be used to kill you. Agents had again infiltrated the country. They would not end the world, no. But they would end your world.

And maybe, if you were a certain kind of child, one of your one of your friends showed you Loose Change, and suddenly you had no idea what to believe. You used to dread the possibility that any building you were in might explode, but now you dreaded the possibility that the people spying on you were also the ones which might one day kill you, for ends you could not understand. And at some point you became aware of The Patriot Act, and you learned of titanic servers, recording so much data, and you also became aware of Anonymous, and Black Hat Hackers, and White Hat Hackers, and data breaches, and, much much later, Wikileaks, which you learned to consider part of the same story.

And maybe, when you were introduced to your first conspiracy theory, you felt the same way you did when you heard about the gun in your friend’s father’s holster, or when you looked out a classroom window and noticed a strange car idling in a distant parking lot, on that day recess had been cancelled, because the “DC Sniper” had started to shoot children.

And as you got older, one of two things happened. Possibility one: your interest in conspiracies and hidden knowledge consumed you, and you became one of the many whose lives were lost in a labyrinth of message boards and chatrooms, and you can barely function because you believe 5G will render the Earth subservient to a race of pedophilic, subterranean reptiloids. The alternative: you learned that steel beams do, in fact, lose integrity at temperatures well below their melting point, you learned that conspiracy theories passed around on the internet rarely hold up to scrutiny, and you learned how to investigate claims well and verify or discard them. But even if you belonged to this latter group, you were still haunted by an imperceptible shadow over your thoughts.

This shadow was especially dark if you grew up, again, near DC, where on the day of Towers, a hole had been blown open in a structure that swarmed with secrets. Maybe your school went there on a field trip, and you were tempted to wander off, but were too frightened. Maybe even today, when you get on the metro, and take the blue line, you watch for who gets off at Pentagon station, and you imagine which halls they take, what lies at their destination.

Doom Patrol (Vol 2.) #38

IV.

· All just listening in the dark. ·

For the past few months, ever since I read the first issue of Strange Skies, my mind has so often turned (or returned) to thoughts of spies, secrets, and stars.

The story begins with the wall.

I’ve been to the Berlin Wall once, extremely briefly, when I was a teenager. “Wall” is a wrong word, because it was really two walls, and the walls themselves weren’t really what we think of when we talk about the Berlin Wall. What was important, what divided people, kept them out or in, was the space between walls. A dead zone. A space, but not a place, because you couldn’t exist there. It was something that abhorred people, that killed anything in it. Even the people who did the killing weren’t really in that space. They were perched above it, in towers, watching.

When I visited, the wall felt to me to be deeply wrong. It wasn’t just because of what it represented, or because of the history there. It wasn’t just the ghosts. It was the rubble that unsettled me. That no-place, the real thing we talk about when we talk about the wall, was gone. When you blow a hole in a vacuum chamber, air spills in, and the emptiness itself is gone. It was like that, at the wall.

When I saw what remained, some part of me was moved, perversely, to want to run away from everyone around me, to look for some space between the piles of rubble, some part of the old wall that had really survived. Maybe you could go there, now, and hide in a spot made to do nothing but kill you, and survive. Maybe you could stay there forever.

Strange Skies Over East Berlin is set in the time before the wall fell. Herring, the man we follow throughout Strange Skies, is one of the few men that can cross that space. He sometimes sends through people, but more typically sends secrets. He’s a spy for America in East Germany. One night, something comes down to Earth, something crosses the vaster, stranger vacuum, the no-space above us, and crashes into East Berlin. Herring is tasked with understanding and revealing whatever secret was contained in that crash.

You can call that secret a UFO, and the being within it an alien, but when you see what walks onto the page, you know that those words, those ideas, fail to describe it. This isn’t Science Fiction; it’s Epistemological Horror. Herring is doomed to fail in his task not because the crashed alien is too powerful, or because the eyes of East Germany are too keen. Herring is doomed because the thing that crashed is unknowable. In the first issue we see that Berlin is almost infested with spies, that they read thousands of letters, listen to thousands of calls, gather so much information that just by sheer volume it is unusable.

If all of their eyes and ears were turned to this thing, it would not matter.

They would fail, and secrets of their own would begin to spill from their mouths.

That’s the one thing we learn of the heavenly thing when Herring first enters the base containing it. We learn not what it is, but what it can do: seize all secrets from your brain and weaponize them. Turn them into a knife that slices through your psyche.

We don’t even know if it’s doing these things on purpose. We can’t apply to it such simple concepts as “will.”

What would you do?

What would you do if one day you woke up and were confronted with something which you could not account for given your entire understanding of reality, and everything in it?

What would you do if some angelic flame-wrapped thing came down from the heavens and turned to you and reached into your skull, and suddenly your tongue betrayed you and spoke aloud every thing you have hidden in your life?

What would you do if every facade of every person around you was wrenched away?

Herring is a spy in East Germany. He is confronted with something that cannot be known. He is confronted with something that can make known everything about him. He is in danger of annihilation.

But what Strange Skies Over East Berlin also suggests, I think, is that in this confrontation Herring is offered a choice. It suggests that there is grace too in what fell from above: he can be something other than a role, a persona, he can be himself, a real person, for the first time in a very long time.

What does that say about Herring?

What does that say about us?

I don’t know.

Join the AIPT Patreon

Want to take our relationship to the next level? Become a patron today to gain access to exclusive perks, such as:

- ❌ Remove all ads on the website

- 💬 Join our Discord community, where we chat about the latest news and releases from everything we cover on AIPT

- 📗 Access to our monthly book club

- 📦 Get a physical trade paperback shipped to you every month

- 💥 And more!

You must be logged in to post a comment.